Edit: This story was awarded 2nd place in the Technical Writing category at the 2017 North American Guild of Beer Writers (NAGBW) awards. While I’m extremely grateful to the judges, it’s humbling yet a li’l embarrassing that the estimable technical beer writer Randy Mosher placed 3rd for this cool story, “Hot Process: Exploring the role of heat in brewing” in All About Beer. Stan Heironymus took 1st place with his story on brewing with honey, also in AAB.

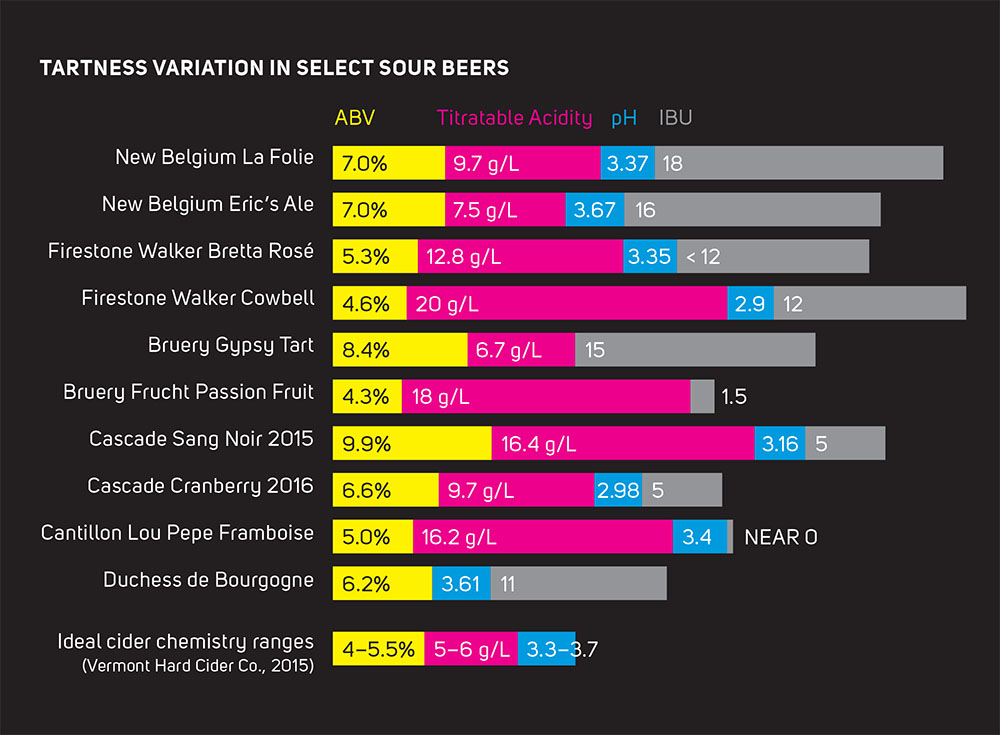

Remember Top Secret? Remember that great song in it, How Silly Can You Get? That’s how I think of a lot of beers. How alcoholic can you get? Brewmeister’s Snake Charmer has an ABV of 67.5% How bitter can you get? Flying Monkey’s Alpha-fornication packs 2,500 IBU. From OG/FG to SRM, brewers have a lot of measurements and acronyms to tell the consumer just how something something is. For sour heads, ours may come in the form of TA. Titratable Acidity. Firestone Walker Brewing isn’t the first to use TA in their lab, but they are the first to put how quantifiably sour their beer is right on the label of their funky Barrelworks offerings.

Now, a quick word about this story on Titratable Acidity just published in the November issue of BeerAdvocate: it’s crazy heavy on the chemistry-spiel, and I barely passed high school chemistry. I do this from time to time–I really challenge myself to wrap my head around a story. I had never heard the word “titratable” or “titration/titrating” before pitching this. I bludgeoned these poor master brewers, master blenders, and folks with Ph.D.s in food and brewing science with questions first so I could begin to understand what’s going on with the acidity in certain beers–specifically what types of acids are present and how they got there–and once I felt semi-comfortable with that, I had to write it up for the readers who didn’t have the same access I got. SO… if you think this story is “TL;DR” just imagine poor little me for whom it was nearly TL;DW. (And here I massively applaud my editor at BA, Ben Keene, for whom this must’ve been challenging to no end but did a masterful job, even if he originally assigned me 1,800 words, then caved and gave me 2,000, and somehow got it way, way down to 2,300!)

(named, presumably, for the Siuslaw National Forest that occupies a tiny part of Alsea’s Benton County) put it on my map.

(named, presumably, for the Siuslaw National Forest that occupies a tiny part of Alsea’s Benton County) put it on my map.